Gil Scott-Heron: Is That Jazz? A book review

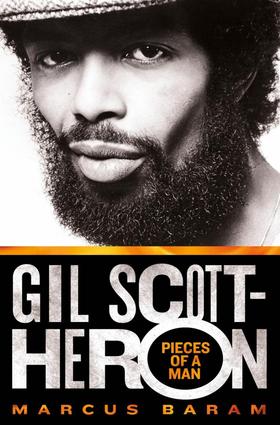

Chroniclers of the life of Gil-Scot Heron (GSH) describe him as a contradiction—the lead evidence is his self-destructive drug use while musically preaching the dangers of drugs to others. Critics also cite parent Gil’s neglect of his children despite having been pained by the absence of his own father. These and other tales of failings and accomplishments are here—the compassion and neglect, the engagement and denial, the creativity and ambivalence. In Marcus Baram’s new book Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man, the stories are supported by 200-plus interviews of family members, school pals, and musical associates. The author speaks of a long term acquaintance with Gil and his interest in writing of this life. A memoir published in 2012 by Scott-Heron and quoted extensively is invaluable in explaining the life decision choices of this complex man.

The young Scottie gave signs of forthcoming promise and conflict. Shortly after his birth, father Gillie, the first black professional soccer player in the USA, left the family home in Chicago for Detroit after job struggles. He found success in a much-heralded league in Europe, but Gil was not to see his father for the next twenty-five years. Gil was sent to live with his grandmother in Jackson, Tennessee. Reading Langston Hughes, he learned of the civil rights struggle; and from Agatha Christie, he was inspired to write detective stories. Gil and two classmates desegregated the local school–the new enrollment: 661 whites, 3 blacks. It was the move at age fourteen to the NY neighborhoods of the Bronx and later Chelsea that was most impressionable. Here Gil learned of the African tradition of passing historical tradition orally–poets would rap their message over rhythmic percussion and strings. This would inspire his song composition style; but first, he wrote a novel, The Vulture, and a book of poems, Small Talk at 125th and Lenox—more testament to his writing talent.

Gil’s songs were saturated with powerful lines of contempt for political figures (Oatmeal Man, Skippy, and Re-Ron), the excesses of capitalism, and oppression. The discography lists social unrest messages “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and “Winter in America,” the drug anthems “The Bottle” and “Angel Dust,” and the anti-consumerism banner “Madison Avenue.” His biting political sarcasm in heavy rhythm song spread from the East Coast college campuses to big city streets, small clubs, and record vinyl. The danceable tunes were released as singles (to please the recording company).

GSH eschewed membership in militant organizations, believing this jeopardized his independence; freedom to express oneself without ideology was important to Gil. He was not hesitant to call out black leaders who put personal gain ahead of the civil rights message. When the woman’s lib and gay rights movements overshadowed the civil rights efforts of blacks, Gil wrote songs of nuclear risk, prison conditions, and unsafe mining practices. To blacks who were critical of Gil’s taking on “white” issues, he explained, “There are a lot of white people in the world who are oppressed. It doesn’t seem to be to anybody’s advantage to just concentrate on areas that affect a narrow part of our community or the community at large.”

Although dubbed by the media “the godfather of rap,” Gil believed many rappers to be lacking full awareness of black history. He was inspired by the Last Poets, but passed the poetry torch to rappers rather reluctantly.

Brian Jackson directed the music on the successful 1970’s Arista recordings—the 10-year period of collaboration and friendship with Gil was a time of focus, creativity, and strong performance. But Jackson walked away, tired of Gil’s unreliability and increasing dominance over song arranging decisions. Following a series of drug possession convictions and prison time, Brian paid Gil a visit to say goodbye: “I love you and have a nice life.” Gil’s response, “Okay, cool.” Displaying an ever-ambivalent attitude, Gil had decided to go-it alone. The addiction continued—a progression from freebasing to crack cocaine.

I am reading when a neighbor passes by and asks, “Good book?” I reply, “You may know him; this is a new biography of Gil Scott-Heron.” “Oh, yeah? He didn’t show up at two concerts I went to—at the Bluebird Theater and The Soiled Dove. It was just before he died; he was strung out!” Tragically and sadly, this may be a common remembrance of Gil Scott-Heron.

Baram, Marcus. Gil Scott-Heron: Pieces of a Man. St. Martin’s Press: New York. 2014.

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!