Johnson Makes Blues Guitar History

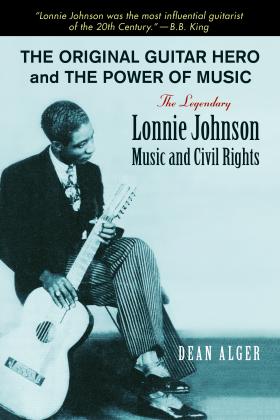

With the book The Original Guitar Hero and the Power of Music: the Legendary Lonnie Johnson, Music, and Civil Rights, Dean Alger promotes legendary status for an early twentieth century New Orleans-born musician. Lonnie Johnson played multiple string instruments–guitar, 12-string guitar, violin, banjo, and mandolin. The story is of a serious under-recognized artist who reached the top of his profession in a steady ascent while recording and performing with blues and jazz artists, including Bessie Smith, Louis Armstrong, and Duke Ellington.

Labelling LJ a “guitar hero” may be the wrong approach; his accomplishments occurred long before the rock guitar era. But, B. B. King supports the drive by naming LJ his guitar-playing inspiration. For Alger and King, the failure of media to rank this guitarist is a travesty. Further testimony has Eric Clapton and Duane Allman being influenced by LJ in that both have named B. B. as influential in their own careers. Do Clapton, Allman, T-Bone Walker, Buddy Guy and Robert Cray also owe LJ a debt of gratitude? The blues music of today is very different from the sounds LJ presents on his resume. But it was LJ who first bent the notes, plugged in his guitar, and played guitar solos in large ensembles performing what came to be known as “jazz blues.

Labelling LJ a “guitar hero” may be the wrong approach; his accomplishments occurred long before the rock guitar era. But, B. B. King supports the drive by naming LJ his guitar-playing inspiration. For Alger and King, the failure of media to rank this guitarist is a travesty. Further testimony has Eric Clapton and Duane Allman being influenced by LJ in that both have named B. B. as influential in their own careers. Do Clapton, Allman, T-Bone Walker, Buddy Guy and Robert Cray also owe LJ a debt of gratitude? The blues music of today is very different from the sounds LJ presents on his resume. But it was LJ who first bent the notes, plugged in his guitar, and played guitar solos in large ensembles performing what came to be known as “jazz blues.

“Alger describes each 78 rpm side or LP song recording as if he was writing liner notes. In the absence of another historical record, a song word or lyric line or intonation becomes the main vehicle for sharing with readers LJ’s musical and non-musical life—the family heartbreaks, lost loves, cities, and travels. From the song lyrics, Alger infers LJ’s thoughts, feelings, and life experience when other sources are absent or incomplete. The book is about song lyrics, instrument sounds, and vocalizing—at times Alger finds the vocals wanting, but never the string playing.

After giving brief references to the civil rights struggle of Blacks in the main text, Alger and publisher deliver a smaller-type appendix titled “Blues, Jazz and Their Significance: Musicians and Civil Rights.” Public displays of mutual appreciation of all forms of music by both the aforementioned Black musicians and the White musicians Jack Teagarden, Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman, and Artie Shaw contributed to improved race relations. Although difficult to measure, the power of music to enhance cultural understanding and racial tolerance is a subject here; and, Alger addresses the refrain, “White guys can’t play jazz.” Tsk, tsk?

Lonnie first played music on a violin in New Orleans and rural Louisiana. His father taught his large family music and instruments and had some playing in a “string band” for local events and on the street corner. By the time he reached his twenties, Lonnie was considered the finest lead guitar player in New Orleans, leaving rhythm playing to others—he may be the “true founding father of lead jazz guitar. “He took that expressive capacity of the violin, including ways to make the instrument give voice to human feelings, and conveyed other aesthetic sound effects, and he transferred it to the guitar. A little later he began developing the interplay of voice and guitar, which became such a prime element of the blues.” Alger has Lonnie as the first master of this art of conveying human feelings with instruments. This book has merit for its tracing of the events that advanced the guitar as the primary instrument in popular music.

In 1926 the recordings of Lonnie Johnson and Blind Lemon Jefferson helped expand the blues listening audience. LJ’s first “A” side was titled “Mr. Johnson’s Blues” and the flip side “Falling Rain Blues.” For the “B” side recording, “. . . with the song’s first notes, (Lonnie) shows how the violin can play some very expressive, crying blues . . . he adds to that a rather unique shuddering effect with his bow and violin that offers another technique for expressing the blues feel via the violin.” A song index lists 90 LJ tunes (with page reference) that are discussed in the book.

The music life story continues with Lonnie doing lead and solo guitar work with Armstrong in December, 1927. Appearing on these recordings are Johnny Dodds with clarinet solo and Kid Ory on trombone. Also in the late 20s period, Lonnie is recording with Bessie Smith (e.g. “Broken Levee Blues”) and Duke Ellington (e.g. “The Mooche”). Days later he was working in a studio with Don Redman and Benny Carter. He was soon accompanying and singing with Victoria Spivey (e.g. “New Black Snake Blues). For Lonnie, this was a time spent establishing his early and lengthy discography while building legendary “guitar hero” status.

Alger, Dean. The Original Guitar Hero and the Power of Music: the Legendary Lonnie Johnson, Music, and Civil Rights. University of North Texas Press: Denton, TX. 2014.

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!