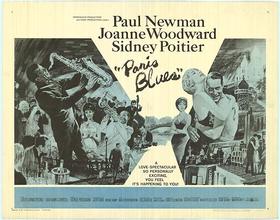

Jazz on Film: Paris Blues – Art, Freedom or Love

Despite being among the greatest of American inventions, jazz has always been a hard way to make a living. Many musicians, from Sidney Bechet and Josephine Baker to Dee Dee Bridgewater and Jerry Gonzalez, have sought a better life for themselves overseas. Some left for artistic reasons, some left because they lost their Cabaret cards, often because of drug use, without which they could no longer be booked in U.S. clubs. Many black jazz musicians left at the height of the Civil Rights movement to find new homes where their race and color were not held against them. It is something of a sad truth that jazz is more welcome and revered in other countries than in America. Kenny Clarke (France), Johnny Griffin (Netherlands and France), Randy Weston (Morocco), Art Farmer (Austria) were among the many who found new homes overseas. For an interesting look into their lives see Bill Moody’s book Jazz Exiles, Americans Abroad (University of Nevada Press, 1993).

Shot in glorious black and white, “Paris Blues” (1961, directed by Martin Ritt) introduces us to trombonist Ram Bowen (Paul Newman) and tenor saxophonist Eddie Cook (Sidney Poitier). They are happily writing music and performing nightly, living a simple life with the proverbial wine, women and song. Ram makes his way to the train station where the jazz giant ‘Wild Man Moore’ played by Louis Armstrong is arriving, and who’s met with an almost Beatlemania level of adulation (talk about a jazz fantasy!). Ram intends to share one of his compositions with the great man.

Enter two young women Lillian (Joanne Woodward) and Connie (Diahann Carroll) on a 12-day holiday. It is Connie that Ram takes an immediate shinning to but in 1961 that kind of film couldn’t yet be made. The powerful interracial moment would come in 1967 with “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” In “Paris Blues,” the relationships between the couples develop instantly, and each falls into an easy familiarity. I thought that the sexual freedom undergirding Joanne Woodward’s character was pretty stunning for that period in time. While Ram and Lillian’s relationship is slightly confrontational Eddie and Connie’s showed a gentler side. Their romances take place in the backdrop of Paris with shots along the bridges on Seine, the stairs at Rue Chappe, and the island Ile de Cygnes. It may be the only film ever set in Paris without a single shot of the Eiffel Tower. The masterful undertones in the Ellington/Strayhorn score add nuance and wistfulness to falling in love in Paris.

Over the course of those days, Connie questions Eddie’s commitment to his music versus the movement. His reply is “Here in Paris I’m Eddie Cook, musician-period; not Eddie Cook Negro musician.” While enjoying each other, Lillian and Ram have a more complicated arc. She lets on she is a divorcee with two children and likes her life in a small town. He tries to tell her that nothing is more important to him than his music, even as he lets her get closer to him. With time running out, love forces the men to choose. Despite the racial struggles that he knows he will return to face, for Eddie is choice is clearly Connie. Lillian offers Ram a deal, to try it for a year and if it doesn’t work she will move (presumably with her children) back to Paris with him. Ram struggles to decide. After a scene where he feels rejected as a serious composer—actually he is told he needs time to study—Ram now chooses Lillian. But he has another change of heart and ultimately opts for his art over his happiness. She tells him “nobody is ever going to be as right for you as me.” Prescient? Married in 1958, Newman and Woodward had one of the great Hollywood marriages until his death in 2008.

The undertone music already mentioned is fantastic throughout the film, and the performance of the band is spirited and swinging. Murray McEachern and Paul Gonsalves ghost for Newman and Poitier. Louis Armstrong’s two cameos are fun and include him bursting into Ram and Eddie’s club to challenge them to a jam session. Paris Blues earned Ellington a second Oscar nomination although curiously, there is no credit for Strayhorn despite the film opening with a version of A-Train.

The stories behind this film are also interesting. Produced by Sam Shaw whose credits as a still photographer include iconic shots of Brando in his torn T-shirt from A Streetcar and Marilyn Monroe’s swirling dress from the Seven Year Itch. The original story was to be based on Shaw’s friend the black collagist Romare Bearden but morphed into one about Paris jazz that was crafted from the novel of the same name by Harold Flender. It centered on the exile experience from Eddie’s perspective. The Hollywood box office wasn’t ready for that type of movie and so a white character was added. Both Ellington and Strayhorn related personally to undergirding themes of freedom inside the story. As musicians, they struggled to be accepted as major, serious composers and as black men in society. Both men were frank in their sexuality; Strayhorn being openly gay at a time when almost no one was and Duke, who was ‘catnip to women,’ was a serial philanderer. Aaron Bridgers who had been Strayhorn’s long-time lover before moving to Paris was cast as the piano player in the group. Ellington thought so highly of the film that he overcame his fear of flying to take his first trip and join Strayhorn in Paris to compose the score. In terms of race relations, all four of the principal actors were strong civil rights and social activists and marched with MLK in 1963.

“Paris Blues” is like many films where the parts are greater than the sum of the whole. It has terrific photography of Paris, likeable stars and wonderful music, even if the story wasn’t all it could be. Bernard Tavernier tried to do something similar with his (1986) film “Round Midnight.” Perhaps there is someone who could build on both movies and reclaim the use of jazz in film to take on major issues of freedom, race, and sexuality and say something in a strong, contemporary voice about artistic expression and what it means to be human.

Music on this feature from the soundtrack to “Paris Blues:” “Paris Steps” and “Battle Royal.”

music from “Paris Blues” soundtrack, clip from movie

9(MDA3NDU1Nzc2MDEzMDUxMzY3MzAwNWEzYQ004))

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!