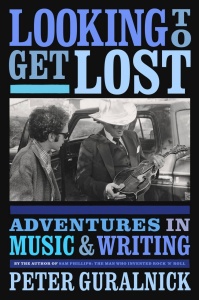

Book Review—Looking To Get Lost: Adventures in Music & Writing

As a young music fan I had preferences. I do not now accept the adage, “I like all kinds of music.” And I did not then. I did not have time for country music with its twangy guitars and corny themes. There was too much blues rock music to push the rest aside. But today I am curious about those discounted, Southern personalities of that former period. Author Guralnick, who has written of careers I supported, presents in this book profiles in chapter-length form of musicians the hip people slighted. They are probably okay people. I single out three chapter profiles for discussion below.

As a young music fan I had preferences. I do not now accept the adage, “I like all kinds of music.” And I did not then. I did not have time for country music with its twangy guitars and corny themes. There was too much blues rock music to push the rest aside. But today I am curious about those discounted, Southern personalities of that former period. Author Guralnick, who has written of careers I supported, presents in this book profiles in chapter-length form of musicians the hip people slighted. They are probably okay people. I single out three chapter profiles for discussion below.

Delbert McClinton. From Fort Worth, Texas. His name suggests “Country singer” but Guralnick paints his profile as an independent bluesman. He formed and disbanded many buddy bands, and stayed true to his roots, not aligning with record companies. He “was always about live music.” Guralnick writes, “He simply stands up there, clasps his hands around the microphone, blows into his harmonica, and wails.”

Quick to express pride in being a financial failure, Delbert honors his roots in the blues. “I’m already a success,” says Delbert, “in doing what I set out to do in the first place–which was just to make a mark, you know. The only thing I haven’t done is make any money.” Delbert seems like the real deal.

Tammy Wynette. Virginia Wynette Pugh was raised on a farm in Itawamba County, Mississippi where she picked cotton and hated butter churning. The close town was Red Bay, Alabama. Married at seventeen and separated shortly after, she completed two beauty college programs to receive licenses to work in both states. But she was soon making it up to Nashville on weekends and luckily met Billy Sherril who first worked for Sam Phillips and then Epic Records. He steered her into recording “Apartment #9,” “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad,” “I Don’t Wanna Play House,” “D-I-V-O-R-C-E”, and the huge success “Stand By Your Man.” Guralnick writes, ” . . . Billy and Tammy agreed (the lyric) was suited to her, all designed to bring out what Sherrill calls the ‘little tear in every word,’ which is the special quality of her voice.”

Explaining the cultural foundation for co-constructing (with Sherrill) her controversial hit, ” . . . back home in Mississippi, you’d stand by a man regardless of what happened because you wouldn’t have any reason or hope to do anything better. Because you (farm wife) have no education, you work in a shirt factory or something, and there’s just no way that you could better yourself if you wanted to. So we just put our ideas down and wrote ‘Stand By Your Man’.”

Bill Monroe. From Kentucky, the Bluegrass state. Monroe became a mandolin player by default, as his older brothers had the guitar and fiddle down pat. Neither of his parents saw him through his teen years, but his musician Uncle Pen moved into the house. “He could fix us breakfast, fix beans and stuff like that. All we had sweet was sorghum and molasses. We just made out. That was hard days, man.” With Uncle Pen–an old-time fiddler–and a black blues player named Arnold Shultz, Monroe’s musical education began with playing square dances. But, for musical inspiration “I love the blues. It’s played a big part in my life.” This was the foundation for the developing father of bluegrass.

Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys travelled from one town to another doing tent shows. He maintained a baseball team in Nashville and took them on the road with his band. There was so much work, there was no need for studio recording. The advent of rock and roll brought it’s challenges, but college campus gigs in the sixties kept the fire burning. Guralnick noted Monroe’s shift to personal songwriting with the near-autobiographical numbers “Uncle Pen,” “Memories of Mother and Dad,” and “I’m On My Way to the Old Home.” Monroe refers to these as the “true, true songs.” Real life as he experienced it.

Creativity. The musicians in these profiles had it, but like others, did not know it for their slow-moving lives shaped by poverty and farm chores. They practiced and developed their melodious voice or instrument proficiency until the generous mentor to guide them into the professional life came along. Productivity came slow, but what else is a farm kid going to do. This phenomena is what seems to have captured Guralnick’s love for his subjects and is conveyed in each episode here. Each individual personality found his/her own way in what appears to be an ordained, though humble origin. They each had an artistic seed and it had to come out.

Guralnick, Peter. Looking To Get Lost: Adventures in Music & Writing. Little, Brown and Company: New York, NY. 2020.

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!