The Contralto and a Tremelo Guitar

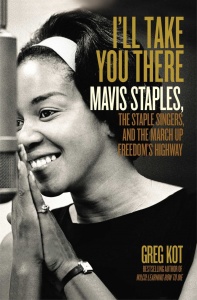

Kot, Greg. I’ll Take You There: Mavis Staples, The Staple Singers, and the March Up Freedom’s Highway. Scribner: New York. 2014.

The young, wholesome face of Mavis Staples graces the cover of this book, but the person who attracted the most attention from me was Pops Staples, the family patriarch. The success of the Staple Singers as stirring gospel performers is attributed to Pops’ direction and management; their spiritual sincerity began with him and stayed with them despite the money-making demands of the pop recording industry, the changing tastes of the black audience, and the gospel police.

Author Greg Kot is a long-term music critic for the Chicago Tribune. In his book you can find in-depth descriptions of the process of recording song tracks and whole albums of The Staple Singers and the recording artist Mavis Staples; the completeness rivals the liner notes written for any gospel, soul, and R&B records–this is a strength of the book. Another highlight is the historical material Kot gathered from two general sources: recent interviews he conducted with family members Pervis, Yvonne, and Mavis Staples; and, the unpublished memoir prepared by Pops Staples. The latter provides accounts of his hardscrabble life in Mississippi, Pops’ working life in Chicago, and family travels to perform in Southern churches—Mavis drove the Cadillac while the family slept, and Pops packed a gun to encourage fair play from festival promoters.

The book begins with an interesting discussion of the early life of Roebuck Staples in the Mississippi Delta. The boy, who as a man was known as “Pops,” grew up in a sharecropping family, absorbing the lifestyle common to rural blacks in the early twentieth century. The slavery-era plantations remained, but the land had been parceled out to tenants who farmed the land for a share of the food crop and little sustenance money. Married at eighteen, Roebuck Staples moved his growing family to Chicago’s South Side like so many other roots musicians seeking improved conditions for his family and professional opportunity.

There is slight mention of Pops working in the awful meat packing plants on the South Side—they were referred to locally as “the Stockyards.” Kot provides no details of Pops’ actual job, but my image of the workplace is of immigrants and the poorly educated working with knives and in freezing meat lockers; read Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle for a muckraker’s account. He also worked in the steel mills of Gary, Ind., another common wage-provider for the unskilled black workingmen of the South Side in the 1950s. On weekends, the musical family performed at Chicago churches and drove hundreds of miles to perform gospel music in the rural churches and cities of the Deep South; e.g. Jackson, Memphis, and Atlanta. Pops played tremolo guitar, and future solo recording star Mavis sang contralto. When the voice of oldest son Pervis changed as a young teen, Mavis, a small person with a big voice, became the lead vocalist. Pops also vocalized, and the three daughters Cleotha, Yvonne, and Mavis provided the harmonies.

Reading along with an increasing regard for the work of Roebuck Staples as patriarch and singing group leader, the warmth turned to chill with the chapter on family tragedy. Pops had left a loaded gun in his home, a home occupied by a daughter dealing with depression. The youngest member of the family went into a back room and shot herself. A weapon meant to defend the family took one member away and emotionally hurt the others. Without the inclusion of this episode in the book, author Kot would have us believe the Staples folks are near perfect; Pervis’ nickname was “Blab” because he talked a lot, but I think that was just his friends having a joke.

The most well-known gospel singer in Chicago and nationally was Mahalia Jackson; she became a friend of the family. In the early years, the Staples could also count as friends and neighbors Sam Cooke, Lou Rawls, and Johnnie Taylor. A frequent visitor from Detroit was Aretha Franklin. The Staples shared the socio-political stage with Martin Luther King and Jessie Jackson. And, the reader is teased with a lengthy account of Mavis’ relationship with the then folk singer Bob Dylan. In addition to Dylan, Levon Helm of the group The Band, David Byrne of Talking Heads, Curtis Mayfield, and Prince provided friendship, songs, and/or produced albums for the Staple Singers and Mavis Staples.

The Civil Rights Movement aided the career of gospel singers. The hymns sung by black church choirs became the songs of the marching protestors. The songs and the singers, like the Staple family members, inspired poor and oppressed people to push the fight for equality and justice. The Staples delivered the message in performance, although the recordings were to take on an increasing number of secular tracks. The spiritual messages and sounds could be found in the underlying tone–the Staple Singers remained a gospel group and interwove spiritual songs into their larger performance repertoire.

When the Staple Singers were signed to a contract with Stax Records by executive Al Bell in 1968, the company star was Isaac Hayes; previous to that, it was Otis Redding. The first two Staples albums, the second a solo album for Mavis, were unsuccessful. Bell elected to move the group from Memphis, where the principle session men were Booker T & the M.G.’s musicians, over to a newly established independent studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Steve Cropper, the young white guitarist for Booker T, came along to produce the new album, We’ll Get Over, as he had done with the group’s first, Soul Folk in Action. The Staples family loved working on the songs, which were a mix of gospel sentiments and also covers of songs popularized by Joe South, Gladys Knight, Sly and the Family Stone, Guess Who and others—the group was transitioning from gospel to pop. For this book Steve Cropper was interviewed by Kot: “If there was a downside to working with them (the Staples), there were restrictions from going all-out at first because Pop wasn’t ready to make the leap to what he considered pop music. . . I should say lyrically reluctant because they had that dance element creeping in with our rhythm section. . . It wasn’t until later with Al Bell that they got more down-and-dirty sounding, with meaningful lyrics, and the hits started to come (139).”

When the Staple Singers were signed to a contract with Stax Records by executive Al Bell in 1968, the company star was Isaac Hayes; previous to that, it was Otis Redding. The first two Staples albums, the second a solo album for Mavis, were unsuccessful. Bell elected to move the group from Memphis, where the principle session men were Booker T & the M.G.’s musicians, over to a newly established independent studio in Muscle Shoals, Alabama. Steve Cropper, the young white guitarist for Booker T, came along to produce the new album, We’ll Get Over, as he had done with the group’s first, Soul Folk in Action. The Staples family loved working on the songs, which were a mix of gospel sentiments and also covers of songs popularized by Joe South, Gladys Knight, Sly and the Family Stone, Guess Who and others—the group was transitioning from gospel to pop. For this book Steve Cropper was interviewed by Kot: “If there was a downside to working with them (the Staples), there were restrictions from going all-out at first because Pop wasn’t ready to make the leap to what he considered pop music. . . I should say lyrically reluctant because they had that dance element creeping in with our rhythm section. . . It wasn’t until later with Al Bell that they got more down-and-dirty sounding, with meaningful lyrics, and the hits started to come (139).”

The family would attribute the song hits to the outstanding musicians at Muscle Shoals—David Hood on bass, Barry Beckett on keyboards, Roger Hawkins, Jimmy Johnson, and Eddie Hinton on rhythm and lead guitar. Mavis put it like this: “That was a rhythm to die for; they were funky, and they helped make us sound funky.” Kot wrote: “Their bond with the Staple Singers was especially tight, due in no small part to the family’s easygoing warmth.” From Johnson: “They were huggers. . . We’d get a hug at the beginning and end of the week.” Johnson’s mom and dad would host meals for all interested, “country-fried beefsteak, cream potatoes, brown gravy, black-eyed peas, and corn on the cob. Her homemade pies rivaled those of Mom Staples (170).”

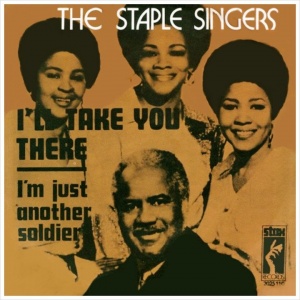

Kot describes Stax executive and record producer Al Bell’s plan at these Muscle Shoals recording sessions: “He (Bell) wanted the Staple Singers interacting with the musicians so there was a genuine dialogue; the rhythm track would be nailed down in tandem with live vocals, and then the Staples would go to Ardent Studios in Memphis to refine and overdub the finished vocals with Bell and engineer Terry Manning.” Two major hits resulted from this combined team effort, “Respect Yourself,” and “I’ll Take You There.” Career success took off from there.

Mavis Staples continues to record solo albums with her band and producers like Ry Cooder, Levon Helm, and Prince. Her 2005 release titled We’ll Never Turn Back fell into my hands unexpectedly. My brother, who worked as a community organizer for a time on the South Side, chose to celebrate the presidential election of Barack Obama by gifting me and others with a copy—it contains many songs of inspiration and hope. Thank you, brother.

Become a Member

Join the growing family of people who believe that music is essential to our community. Your donation supports the work we do, the programs you count on, and the events you enjoy.

Download the App

Download KUVO's FREE app today! The KUVO Public Radio App allows you to take KUVO's music and news with you anywhere, anytime!